Staff Reporter

Trucking Offered Measure of Stability in Diesel Revenue as Pandemic Caused Gas Tax Revenue to Tank

[Ensure you have all the info you need in these unprecedented times. Subscribe now.]

As the coronavirus pandemic hit the nation with full force this spring, many people, some for the first time, appreciated truck drivers.

They paused to consider who was hauling the paper towels, hand sanitizer and disinfectant spray they had come to prize.

But in addition to essential supplies, truck drivers provided a service that is less tangible but no less important: boosting revenue for state transportation departments.

Good thing they did.

Many states instituted stay-at-home orders in hopes of diminishing the impact of the pandemic, triggering a sharp drop in overall traffic levels as commuters worked from home and scuttled vacation plans.

Carl Davis, research director at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, said the drop in fuel tax revenue was inevitable since people also had to cut travel for leisure activities.

“Especially in the spring, it’s clear that driving just cratered,” Davis told Transport Topics. “Folks are paying a lot less in fuel taxes.”

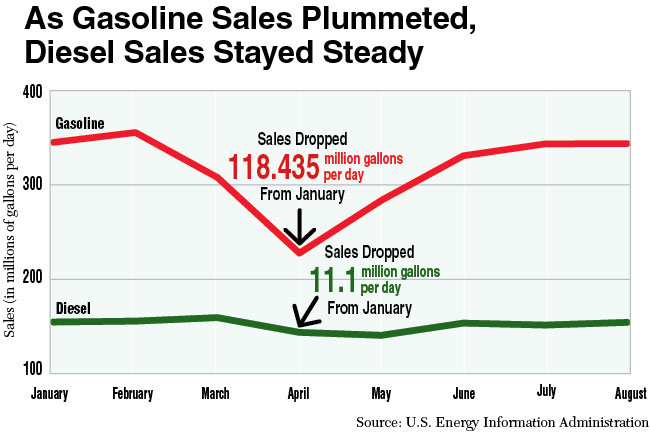

Though the loss of revenue from gasoline taxes ultimately caused a steep decline in funding streams that states badly need, the financial picture from diesel tax revenue generated by trucking looks less bleak. That’s because when others stayed home and avoided filling up their tanks, truckers kept hauling and purchasing diesel — pumping money into states’ accounts.

But the offset isn’t enough. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials estimates a loss of $16 billion for state departments of transportation in fiscal 2020 alone.

Tymon

“It’s been an incredibly hard time, these last five to six months, for state DOTs and transit agencies because the revenue isn’t coming in the way that they had planned for it to come in at the beginning of the year,” AASHTO Executive Director Jim Tymon said.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, gasoline sales sank to about 228.2 million gallons per day on average in April compared with about 368.5 million gallons the same month last year. For ultra-low-sulfur diesel, the outcome wasn’t so severe. Sales dropped to just about 143.5 million gallons per day in April compared with about 159.5 million gallons in April 2019.

The last time ultra-low-sulfur diesel sales were so low was January 2017, when sales dropped to 138.9 million gallons per day. (The comparatively mild winter contributed to lower expenditures related to heating fuels.) EIA data shows gasoline sales in April 2020 were the lowest recorded since 1983, when the administration began collecting such data.

On the Road Again

State transportation officials noted the change.

“As we watch traffic patterns, the percentage decrease in trucks [is] significantly less than the percentage decrease in passenger vehicles over the course of COVID,” Wyoming DOT Director Luke Reiner told TT.

Scott Manning, Indiana DOT spokesman, observed a quicker rebound in truck traffic than passenger vehicle traffic. In the early days of the pandemic, Manning said truck and passenger vehicle traffic dropped sharply. However, truck traffic started climbing back quickly and, within 30 days, had reached levels close to the normal baseline of about 27 million vehicles miles traveled daily.

By early September, Manning said truck traffic levels were about 5% higher than normal. On average, Indiana collects approximately $30 million monthly in diesel tax revenue. An increase of 5% in truck traffic translates to potentially about $1.5 million in additional diesel tax revenue per month above the baseline.

Traffic on I-65 in Jeffersonville, Ind. (John Sommers II for Transport Topics)

At its lowest point, passenger vehicle traffic in Indiana tumbled to about 55% below normal levels (average daily vehicle miles traveled for passenger vehicles is approximately 204 million). As of early September, it still was down about 8%.

Manning said INDOT estimates revenue for the year to be down by about 15%, which translates to approximately $145 million.

In some states, truck traffic volume has been steady, lifting state revenue.

For example, in Idaho, net special fuel tax revenue directed to the Highway Distribution Account was $62.2 million between January and August, leading to an increase of $818,100 from the same period in 2019. Special fuel refers primarily to diesel but also includes compressed and liquid natural gases. But net gasoline tax revenue directed to Idaho’s Highway Distribution Account was $142.7 million between January and August, a $6.1 million decrease from the same period last year.

In Oregon, revenue tied to the state’s specific tax on heavy-duty trucks has proved more stable than other funding sources. Travis Brouwer, assistant director for revenue, finance and compliance at Oregon DOT, compared the primary sources of the State Highway Fund to a “three-legged stool of revenue” supported by the motor fuels tax of 36 cents a gallon on gasoline, driver and vehicle fees that include transactions such as license renewals, and taxes on heavy trucks such as the weight-mile tax.

Oregon’s weight-mile tax applies to vehicles weighing more than 26,000 pounds that are involved in commercial operations on public roads. Tax rates vary depending on the weight of the vehicle. An 80,000-pound truck would be charged $21.50 per 100 miles traveled.

READ MORE: States Take Action as COVID-19 Chokes Revenue Streams

According to Brouwer, revenue from the weight-mile tax has been “remarkably steady” compared with the other two legs of the stool. From January through April 2019, weight-mile tax receipts totaled $113 million. Over that same period in 2020, actual tax receipts totaled $124 million, marking a 9.5% increase from 2019 figures.

Oregon DOT’s chief economist, Daniel Porter, explained that the 2020 results reflect a weight-mile tax increase that went into effect in January. Factoring in the tax increase and adjusting to more fairly examine the two years, weight-mile tax receipts from January through April 2020 would have totaled $119 million, which is a 5.4% increase.

“It does seem to give some sort of indication that people are heavily reliant on trucks to move goods,” Brouwer said. “Typically, we find that trucking activity is fairly cyclical of the economy. You would expect in a major downturn like we see today that people would be putting off major purchases. We just have not seen the economy translate into less trucking activity.”

During the height of the pandemic this spring, Brouwer said driving was down 40%-50% compared with previous years. As of late August, driving levels were down about 10% from levels recorded in previous years. The number of gallons of fuel sold in April was down 33%, Brouwer said.

According to Porter, 149.8 million gallons of taxable gasoline and diesel were sold in April 2019; 100.6 million gallons were sold in April 2020. Oregon Driver and Motor Vehicle Services revenue also has dropped due to offices shuttering for a couple of months. Although the offices have reopened, Brouwer said social distancing measures have placed some constraints on service.

Fuel Tax Rebound in Flux

Despite trucking yielding some stability for diesel tax revenue, states’ piggy banks still are suffering because of the pandemic.

North Carolina DOT estimated COVID-19 cost the agency $300 million in revenue over April, May and June. As of early July, Pennsylvania DOT estimated an overall revenue drop of about $800 million. Michigan DOT funding is projected to be down $94 million in fiscal 2020 revenue.

AASHTO estimates that state departments of transportation need $37 billion through fiscal 2024 to offset revenue losses.

The association and 87 other industry groups wrote congressional leaders Sept. 9 asking them to pass legislation to support state and local agencies that are hurting financially because of the pandemic. Specifically, they asked for legislation that includes a one-year extension of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act of 2015 with increased investment levels, emergency federal funding for state departments of transportation and public transit agencies and provisions to ensure the solvency of the Highway Trust Fund for at least the duration of the extension.

“We’re just really hopeful that Congress is able to come in and provide funding so that state DOTs and transit agencies can continue to do the work that they had planned to do at the beginning of the year,” said AASHTO’s Tymon.

Richard Auxier, senior policy associate at the Tax Policy Center, agreed, saying the situation for fuel tax revenue is particularly grim.

“You’re seeing particular drops in transportation funding resources for these states, and the federal government absolutely should step in and help out,” he said.

He also emphasized the impact of the pandemic on basically every tax at the state and local level.

“People have lost their jobs, so they have less income to pay income taxes; they have less earnings to pay for sales taxes. Hotels don’t have customers, so there’s fewer hotel taxes,” Auxier said. “Just because everything is bad doesn’t mean some things aren’t worse.”

In addition to federal aid, another unknown factor lingers: the coronavirus itself.

According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cases of COVID-19 in mid-September marked a decline from levels recorded in mid-July. However, by mid-October, the encouraging trend had started to reverse. On July 17, CDC recorded a seven-day moving average of 65,339 cases. On Oct. 17, the seven-day moving average was 55,232 cases, an increase from the seven-day moving average of 39,502 cases recorded Sept. 17.

Davis said, depending on the severity of the virus this fall, people could retreat from the roads once more and states could experience large dips in revenue all over again.

“If we see a lot of spread, then we could see reductions in traffic if we start to see mandatory lockdowns because things have gotten out of control,” Davis said. “I don’t think there’s any question that there’s still a lot of risk out there. It’s entirely possible that things could get worse.”

Want more news? Listen to today's daily briefing:

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Alexa | Google Assistant | More